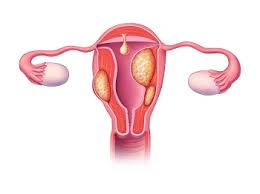

Years ago, when I was a young woman in my 20s, my mother had a fibroid in her uterus. Or, at least that was the way she explained it. Come to think of it, she didn’t explain. Rather, she simply announced she’d had it removed. My brother and I, both medically ignorant at the time, had no idea why that was such a big deal.

In the intervening decades, I’ve learned a lot. Most of that medical knowledge has come from researching for the blog. That’s how I learned that a fibroid is a tumor or, as Johns Hopkins puts it:

“Fibroids are growths made of smooth muscle cells and fibrous connective tissue. These growths develop in the uterus and appear alone or in groups. They range in size, from as small as a grain of rice to as big as a melon. In some cases, fibroids can grow into the uterine cavity or outward from the uterus on stalks.”

Notice the word tumor wasn’t used in this definition. It didn’t have to be because a tumor as defined by my all-time favorite dictionary, the Merriam-Webster, is:

“an abnormal benign or malignant new growth of tissue that possesses no physiological function and arises from uncontrolled usually rapid cellular proliferation”

Since they have no function and grow in the same way as cancer does, are they cancerous? Not according to Planned Parenthood, who also offers us the symptoms:

“Uterine fibroids are almost never cancerous, and they don’t increase your risk for getting other types of cancer. But they can cause pelvic pain, heavy period bleeding, bleeding between periods, back pain, and in some cases, infertility or miscarriages. However, many people with fibroids don’t have any symptoms at all.”

My mother was not the type to want to know how the fibroid developed. As most people did 50 years ago, she just wanted it gone. But you might want to know. WebMD explained:

“Experts don’t know exactly why you get fibroids. Hormones and genetics might make you more likely to get them.

Hormones. Estrogen and progesterone are the hormones that make the lining of your uterus thicken every month during your period. They also seem to affect fibroid growth. When hormone production slows down during menopause, fibroids usually shrink.

Genetics. Researchers have found genetic differences between fibroids and normal cells in the uterus.

Other growth factors. Substances in your body that help with tissue upkeep, such as insulin-like growth factor, may play a part in fibroid growth.

Extracellular matrix (ECM). ECM makes your cells stick together. Fibroids have more ECM than normal cells, which makes them fibrous or ropey. ECM also stores growth factors (substances that spur cell growth) and causes cells to change.”

Let’s get back to Mom wanting it gone. The question here is how? It turns out there are many, many different methods from different types of ablations, surgeries, and medications.

I know you want to know what this has to do with chronic kidney disease. That is actually what I wanted to know, too. According to The National Library of Medicine:

“Uterine fibroids constitute the most common tumor in women of reproductive age …. Significant morbidity secondary to fibroids is a rare event; however acute complications from fibroids may include thromboembolic events, acute torsion of pedunculated fibroids, acute abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, intra-abdominal bleeding, acute urinary retention, and renal failure. [Gail here: I bolded that.] Uterine fibroids are associated with obstructive renal failure as they can physically compress the ureters, leading to acute urinary retention and postrenal nephropathy.”

I get it, but it took me a while to figure out what this meant. So I looked for a different, more easily understood explanation… and found it on Fibroids.com:

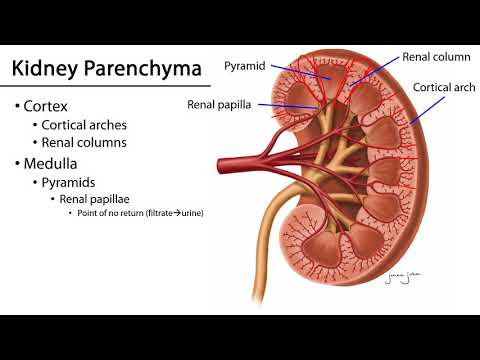

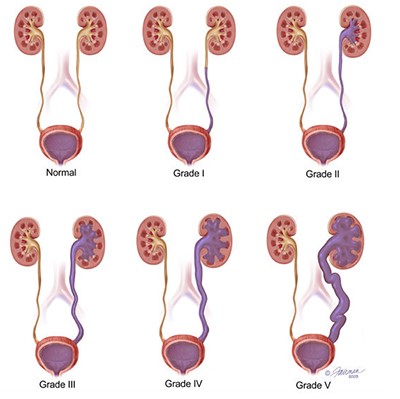

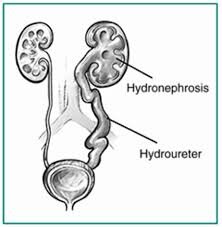

“Although fibroids are made of muscle tissue found in the uterus, they can outgrow the space within the uterine walls and expand to a size large enough to affect the ureter. The ureter is the tube that connects the bladder and the kidney. When fibroids down [sic] on the ureter, the kidneys swell and develop a condition known as hydronephrosis.

Hydronephrosis is often associated with painful urination, an increased urge to urinate, as well as flank and back pain. In more severe cases, permanent kidney damage may also occur. If you are currently experiencing any of these symptoms or suspect your kidneys may be at risk due to your fibroids, consult with your doctor immediately.”

Talkingfibroids,com tells us more about hydronephrosis:

“But if hydronephrosis persists for a long time, the nephrons (kidney cells) can die, and the result can be irreversible kidney damage. Even if the obstruction to the ureter is eventually removed, a kidney that has gotten to this point will not regain function.”

Hmmm, there must be a way to prevent this. I searched and searched until I found what I was looking for on India’s GAURI – Guna Associates in Urogynecology & Research for Incontinence:

“The removal of fibroids is crucial for those suffering kidney complications due to fibroids. Despite the prevalence of fibroid surgery like a hysterectomy or myomectomy [removal of only the fibroid], there is a less invasive procedure called uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) that eliminates the scars and trauma associated with surgery.

Fibroid embolization works by reducing the larger fibroid that is pushing on the ureter and causing kidney problems. It provides a quick and effective procedure with no chance of regrowth of the fibroid. By shrinking the fibroid instead of removing it, patients experience a quick and effective procedure.”

While that may sound scary, remember that surgery is another way to deal with fibroids but UFE is less invasive. There is also medication, but please do not take NSAIDS. That stands for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and, as CKD patients, is not for us. And let’s not forget ablation.

As for diagnosing hydronephrosis, the usual blood and urine tests plus an ultrasound does the trick. The ultrasound will let you see if the kidney is swollen. The urine test will rule out infection or urinary stones. And the blood test will evaluate your kidney function. I wonder whether Mom underwent these tests.

Until next week,

Keep living your life!