You know, in addition to being National Kidney Month, March is also National Woman’s Month. Once again, I decided to combine the two and write about women in nephrology. Nefrologia [English edition] started us off with names you may or may not recognize:

“ Internationally, in an attempt to highlight the work of women in the scientific field, the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) wanted to pay tribute to women who had collaborated closely in the development of the specialty…

Dr Josephine Briggs, responsible for research at the US National Institutes of Health in the 1990s on the renin-angiotensin system, diabetic nephropathy, blood pressure and the effect of antioxidants in kidney disease.

Dr Renée Habib (France), a pioneer of nephropathology in Europe. She worked with the founders of the ISN to establish nephrology as a speciality.

Dr Vidya N Acharya, the first female nephrologist in India inspiring the study of kidney diseases, dedicating her research to urinary infections and heading a Nephrology department in Mumbai.

Dr Hai Yan Wang, head of department and professor of Nephrology at the Peking University First Hospital since 1983, president of the Chinese Society of Nephrology and editor of Chinese and international nephrology journals.

Dr Mona Al-Rukhaimi, co-president of the ISN and leader of the working group on the KDIGO guidelines in the Middle East, as well as a participant in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.

Dr Saraladevi Naicker, who created the first training programme for nephrologists in Africa and the Kidney Transplant Unit at Addington Hospital.

Dr Batya Kristal, the first woman to lead a Nephrology department in Israel and founder of Israel’s National Kidney Foundation. She conducts her current research in the field of oxidative stress and inflammation.

Dr Priscilla Kincaid-Smith, head of Nephrology at Melbourne Hospital, where she promoted the relationship between hypertension and the kidney and analgesic nephropathy. The first and only female president of the ISN, she empowered many other women, including the nephrologist Judy Whitworth, chair of the World Health Organization committee.”

I turned to BMC Nephrology to learn a bit about another woman in nephrology, Dr. Natalia Tomilina. This is from an interview with Dr. Tomilina:

“For me specializing in nephrology happened by chance. After graduating from university, I worked as a general practitioner, and very soon realized that I needed something more than just routine clinical practice; I needed to grow professionally. In 1962–1963 the hospital where I worked introduced a nephrology program. It was not yet a nephrology unit, just 20 beds on the internal medicine floor for patients with kidney diseases. At the time, nephrology as a specialty was only starting to be recognized both in the Soviet Union and in other countries. I was lucky to have met Professor Maria Ratner, who invited me to work with her. I could have moved to the hospital’s research institute, but it seemed to be less interesting, so I chose nephrology and Professor Ratner became my mentor. I found it fascinating, and I have continued to be fascinated by nephrology all my life….”

More recently, as I wrote in March 29’s 2021 blog:

“Dr. Vanessa Grubb first approached me when she was considering writing a blog herself. I believe she’s an important woman nephrologist since she has a special interest in the experiences of Black kidney patients. Here is what University of California’s Department of Medicine’s Center for Vulnerable Populations lists for her:

‘Dr. Vanessa Grubbs is an Associate Professor in the Division of Nephrology at UCSF and has maintained a clinical practice and research program at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital since 2009. Her research focuses on palliative care for patients with end-stage kidney disease. She is among the 2017 cohort for the Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholar Leadership Program, an initiative designed to identify, cultivate and advance the next generation of palliative care leaders; and the 2018 California Health Care Foundation’s Health Care Leadership Program.

Her clinical and research work fuel her passion for creative writing. Her first book, HUNDREDS OF INTERLACED FINGERS: A Kidney Doctor’s Search for the Perfect Match, was released June 2017 from Harper Collins Publishers, Amistad division and is now in paperback.’ [Gail here: Dr. Grubbs writes the blog, The Nephrologist; has the YouTube channel, Real Kidney Talk with The People’s Nephrologist; and is an advocate with her Black Doc Village.]

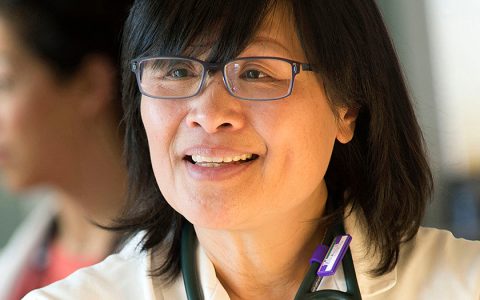

I think Dr. Li-li Hsiao should also be included in today’s blog since she has a special interest in the Asian community and their experiences with kidney disease. The following is from the Boston Taiwanese Biotechnological Association:

‘…. She is the Director of Asian Renal Clinic at BWH; the co-program director and Co-PI of Harvard Summer Research Program in Kidney Medicine. She is recently appointed as the Director of Global Kidney Health Innovation Center. Dr Hsiao’s areas of research include cardiovascular complications in patients with chronic kidney disease; one of her work published in Circulation in 2012 has been ranked at the top 1% most cited article in the Clinical Medicine since 2013. Dr. Hsiao has received numerous awards for her outstanding clinical work, teaching and mentoring of students including Starfish Award recognizing her effective clinical care, and the prestigious Clifford Barger Mentor Award at HMS. Dr. Hsiao is the founder of Kidney Disease Screening and Awareness Program (KDSAP) at Harvard College where she has served as the official advisor. KDSAP has expanded beyond Harvard campus. Dr. Hsiao served in the admission committee of HMS; a committee member of Post Graduate Education and the board of advisor of American Society of Nephrology (ASN). She was Co-Chair for the ‘Professional Development Seminar’ course during the ASN week, and currently, she is the past-president of WIN (Women In Neprology [sic])’”

Just in case you wondered, Zippia [billed as the job experts] showed 47.37% of nephrologists were female as of 2021. And, yes, they did earn less than their male counterparts: 88 cents to the male’s dollar. From all the different sites I looked at, there is still a pay gap between the two genders. All I have to say about that is, “Huh? This IS 2024, isn’t it?”

Until next week,

Keep living your life!