How many times have you heard this as a young single person? Not too many, I hope. I can clearly remember feeling terrible upon hearing this, “It’s not you; it’s me.” Worse yet when I was the one saying it. It did seem necessary all that long ago. Read on and you’ll find out what this has to do with National Donor Month.

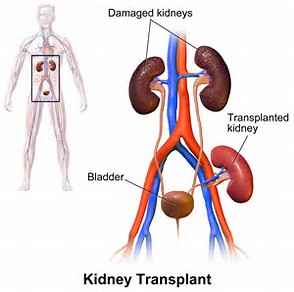

As far as incompatible, in this case, I don’t mean you and me. [Although that could be true.] I mean a kidney transplant between two people who are not a match. Unsurprisingly, this is called an incompatible kidney transplant and you just might call it old fashioned since paired kidney donations have appeared. Let’s see what we can find out about incompatible donation anyway.

My old friend, The Mayo Clinic, offers the following:

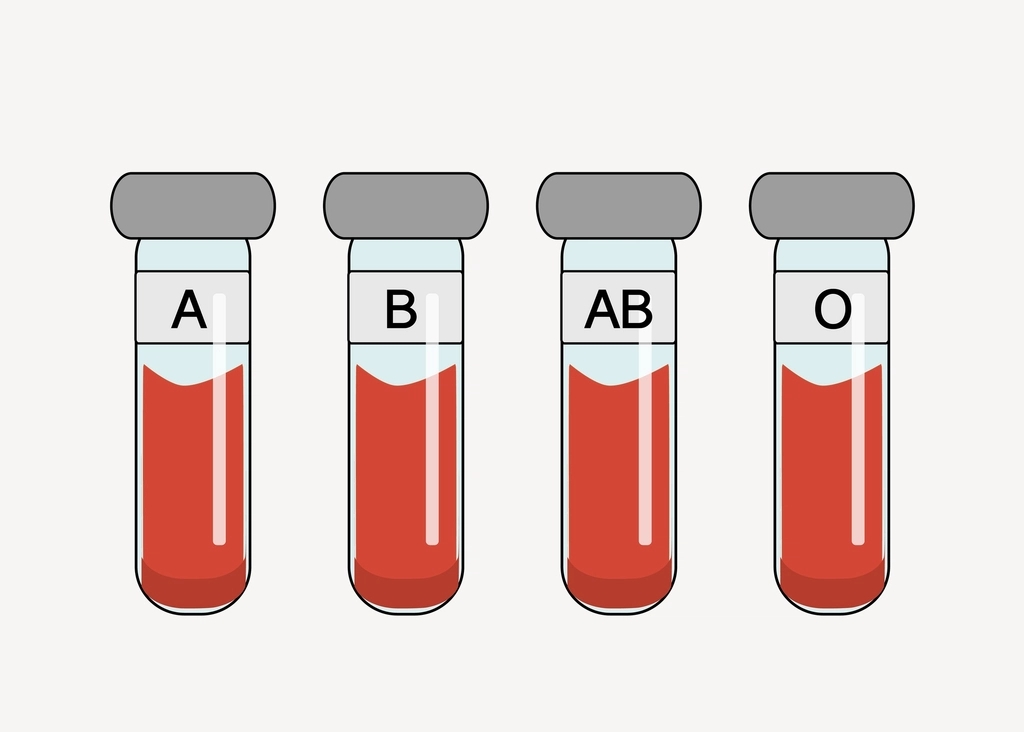

“In the past, if your blood contained antibodies that reacted to your donor’s blood type, the antibody reaction would immediately cause you to reject your transplant. This would prevent a successful transplant. Back then, the only option was to identify recipient-donor transplant pairs with compatible ABO blood types.

Over the years, advances in medicine made ABO incompatible kidney transplant possible between some recipients and living donors. The option of having a living donor with a different blood type reduced the time on a waiting list for some people.

With an ABO incompatible kidney transplant, you receive medical treatment before and after your kidney transplant to lower antibody levels in your blood and reduce the risk of antibodies rejecting the donor kidney. This treatment includes:

- Removing antibodies from your blood (plasmapheresis)

- Injecting antibodies into your body that protect you from infections (intravenous immunoglobulin)

- Providing other medications that protect your new kidney from antibodies) [stet.]”

I don’t know that I’d want to go through all this in addition to the bodily trauma of having a new organ in my body. Then again, knowing me, I’d probably have jumped at the chance if that was the only way for me to stay alive. [Hence, my eagerness to endure chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation to eradicate that nasty pancreatic cancer from my body.]

I do know that I needed more information on plasmapheresis since it was a new concept for me. The National Kidney Foundation did not disappoint:

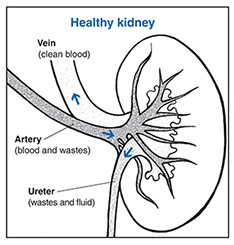

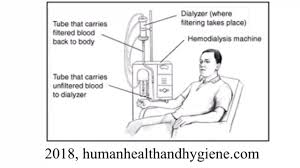

“Plasmapheresis is a process that filters the blood and removes harmful antibodies. It is a procedure done similarly to dialysis; however, it specifically removes antibodies from the plasma portion of the blood. Antibodies are part of the body’s natural defense system which help destroy things that are not a natural part of our own bodies, like germs or bacteria. Antibodies against blood proteins can lead to rejection after a blood-type incompatible transplant. In severe cases, this could cause the kidney transplant to fail. Plasmapheresis before transplant removes antibodies against the donor blood-type from the recipient, so they can’t attack and damage the donated kidney.

Depending on the antibody levels and the transplant center protocols, a medicine to keep more antibodies from forming may also be administered intravenously. In rare cases, the patient’s spleen is removed using minimally invasive surgical technique to keep antibody levels low.

After the transplant, the patient may require additional plasmapheresis treatments before discharge from the hospital. He or she will then take the similar immunosuppression medications as patients receiving a blood type compatible kidney. At some centers, a biopsy may be done soon after transplant to ensure antibodies are not causing rejection of the transplanted kidney.”

I was having a pretty hard time figuring out when and how incompatible transplants started being used until I hit upon the World Journal of Transplantation:

“Principally after 1998, there was a worldwide increase in the rate of kidney transplantations from living donors that involved ABOi. This fact may be principally ascribed to four factors. (1) Since 1998, our knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of ABMR has substantially improved. (2) By the beginning of 2000, Japanese authors published excellent results in renal transplantations involving ABOi … although the main limitation of the Japanese strategy was the splenectomy associated with their pretransplantation protocol. (3) Later, Johns Hopkins University and the Mayo Clinic in the United States documented the possibility of performing such transplantation without splenectomy with the administration of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab [RTX]. (4) Finally, Swedish authors developed a new technique that demonstrated outcomes in renal transplantation involving ABOi that were similar to the outcomes of standard renal transplantation….”

Wait a minute. What is this splenectomy of which they speak? Oh, right, I had one during my cancer surgery. Welcome back to my long absent favorite dictionary, the Merriam-Webster, for the definition: surgical removal. Now, what’s a spleen? Thank you to Medical News Today for answering my question:

“The spleen’s main roles are:

- filtering old or unwanted cells from the blood

- storing red blood cells and platelets

- metabolizing and recycling iron

- preventing infection

The spleen filters the blood, removing old or unwanted cells and platelets. As blood flows into the spleen, it detects any red blood cells that are old or damaged. Blood flows through a maze of passages in the spleen. Healthy cells flow straight through, but those considered unhealthy are broken down by large white blood cells called macrophages.

After breaking down the red blood cells, the spleen stores useful leftover products, such as iron. Eventually, it returns them to the bone marrow to make hemoglobin, the iron-containing part of blood,

The spleen also stores blood cells that the body can use in an emergency, such as severe blood loss. The spleen holds around 25-30% of the body’s red blood cells and about 25% of its platelets.

The spleen’s immune function involves detecting pathogens, such as bacteria, and producing white blood cells and antibodies in response to threats.”

No wonder I’m so tired all the time. Especially if we add my chronic kidney disease stage 3B and sleep apnea. Yuck!

Oh, one last note. Remember, incompatible transplant is not used as much these days since paired donations and transplant chains have come into use.

Until next week,

Keep living your life!