There’s a word banging around in my brain. Although I’ve looked it up several times, I still am not quite sure what it means or how to use it. Why not come along with me for what I’m hoping is the last time of figuring it out? Whoops, forgot to tell you what the word is. It’s amyloidosis.

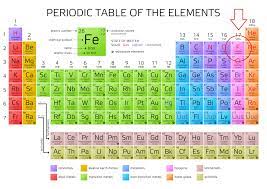

I vaguely thought I remembered it was something on a blood test. I vaguely thought wrong. Okay, let’s go to the experts then. verywellhealth had this information:

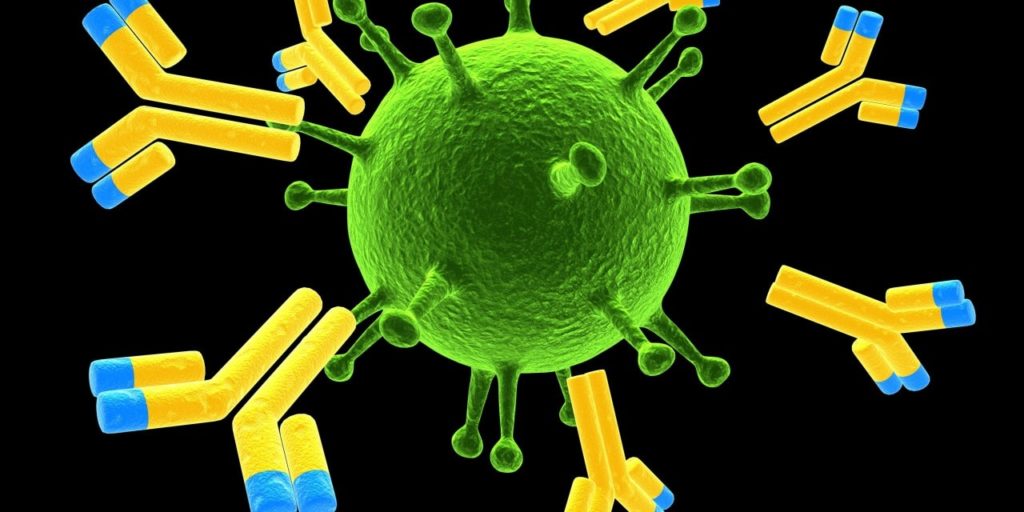

“ Amyloidosis is sometimes called a protein misfolding disorder, in which misfolded [Gail here: never heard of this before. Have you?] proteins are the main reason the condition develops….

The specific protein involved differs between types of amyloidosis.

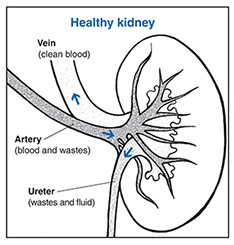

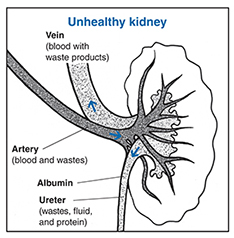

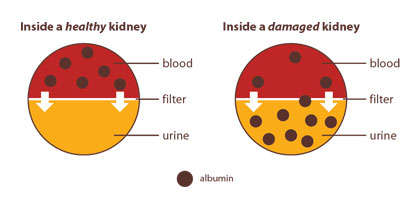

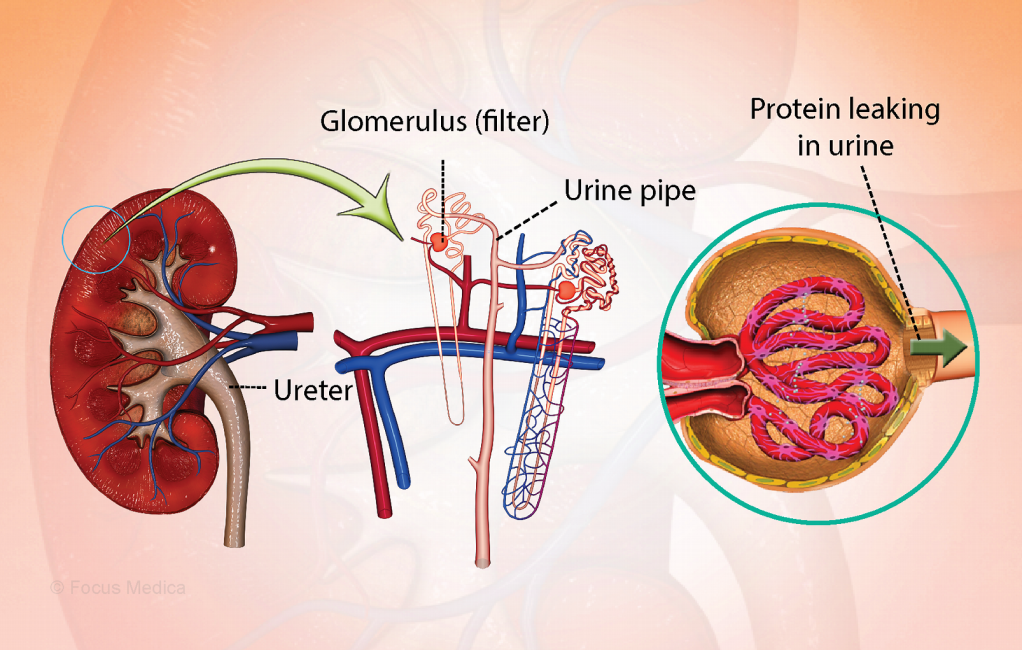

The normal versions of amyloid proteins typically have jobs in the body, from supporting immunity to regulating fluid balance and body processes. When the normal proteins finish their assigned jobs, they leave the bloodstream. But with amyloidosis, they misfold, take on abnormal shapes, and get deposited into the organs.

Amyloidosis is either systemic (widespread or affecting the whole body) or localized to one body area, and there are multiple subtypes.

Systemic amyloidosis is more common and can affect multiple organs and body tissues…. Left untreated, it can lead to organ damage. Localized amyloidosis will affect one organ or only one area of the body.”

That sounds terrible. Of course, the next question I had – since it isn’t part of a blood test as I’d originally thought – was: Are there symptoms? How do you know if you have amyloidosis? WebMd was right there with the answer:

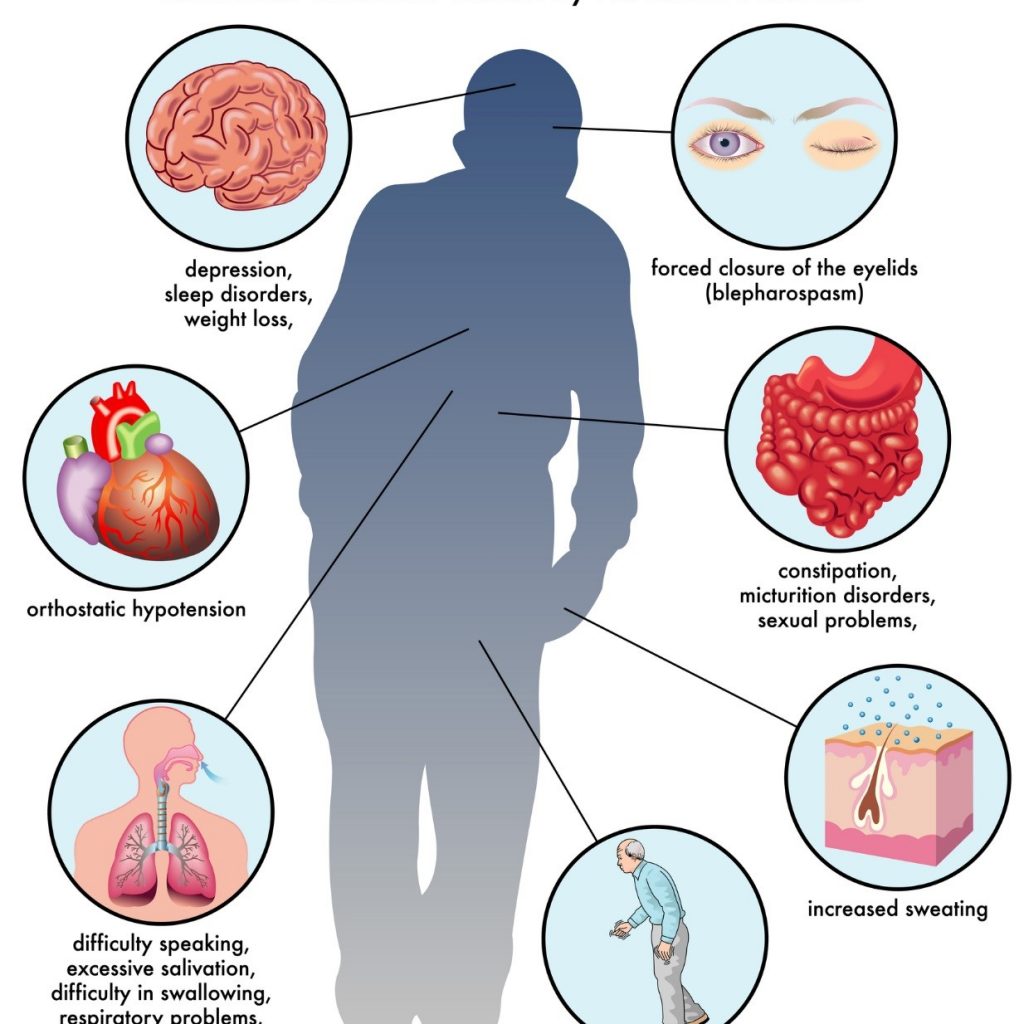

“Symptoms of amyloidosis are often subtle. They can also vary greatly depending on where the amyloid protein is collecting in the body. It is important to note that the symptoms described below may be due to a variety of health problems. Only your doctor can make a diagnosis of amyloidosis.

General symptoms of amyloidosis may include:

- Changes in skin color

- Severe fatigue

- Feeling of fullness

- Joint pain

- Low red blood cell count (anemia)

- Shortness of breath

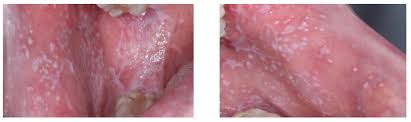

- Swelling of the tongue

- Tingling and numbness in legs and feet

- Weak hand grip

- Severe weakness

- Sudden weight loss”

Like many other people I’m certain, I have several of these symptoms. Therefore, I’m going to bold the warning above:

It is important to note that the symptoms described below may be due to a variety of health problems. Only your doctor can make a diagnosis of amyloidosis.

I don’t know about you, but that gives me a bit of relief. Yet, I still want to know how my doctor can diagnose amyloidosis. I turned to Johns Hopkins Medicine for the answer:

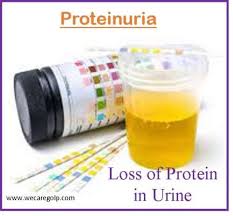

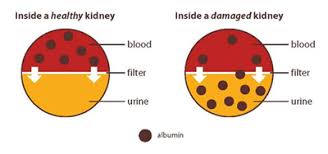

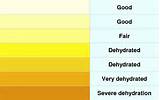

“To see if you have amyloidosis, your doctor will likely order tests. A urine test and a blood test may be followed by one or more imaging procedures to take a look at your body’s internal organs, such as an echocardiogram , nuclear heart test or liver ultrasound . A genetic test may be necessary to see if you have the familial form of amyloidosis.

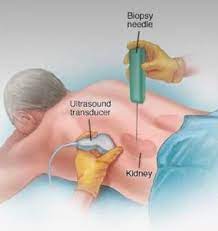

You might undergo a biopsy, where the doctor takes a small sample of your bone marrow or another organ to examine under the microscope.”

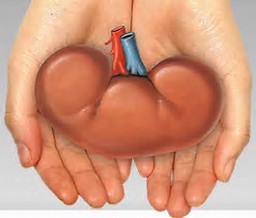

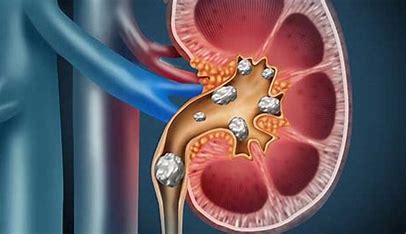

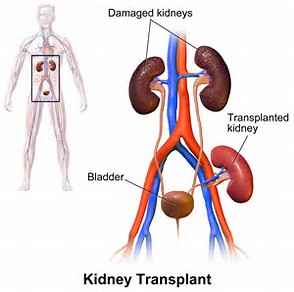

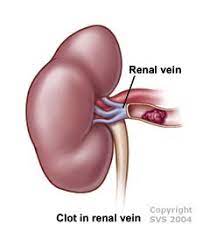

Wait a minute. I got that you may have the symptoms, you see your doctor, and she/he runs tests. I’ve been reading that there’s no cure. I’ve also been reading that the kidneys are affected in several types of amyloidosis. What now? Healthline suggested these treatments:

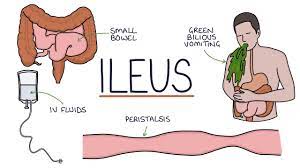

“These medications can be used to help control amyloidosis symptoms:

- pain relievers

- drugs to manage diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting

- diuretics to reduce fluid buildup in your body

- blood thinners to prevent blood clots

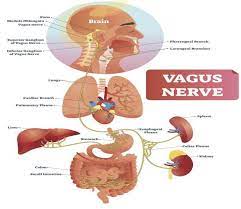

- medications to control your heart rate”

Of course, I became curious about the different types of amyloidosis. Thank you to the Mayo Clinic for this information:

“Types of amyloidosis include:

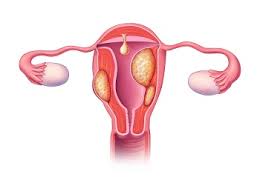

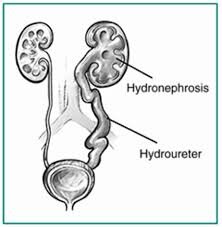

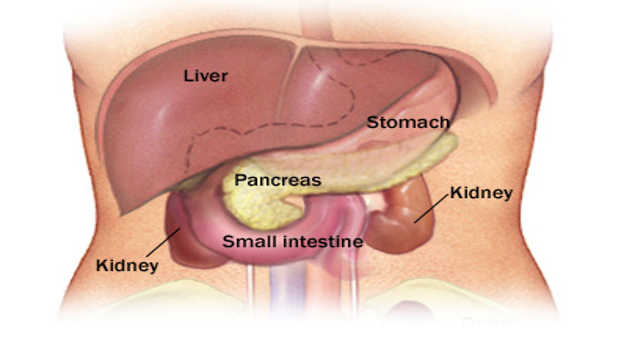

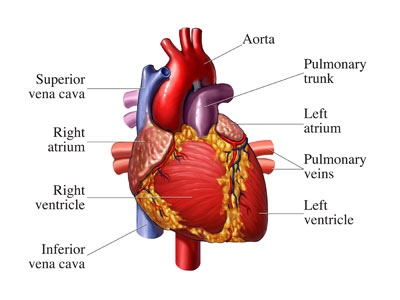

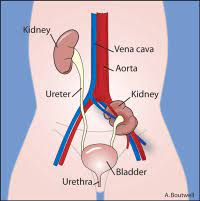

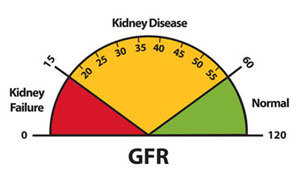

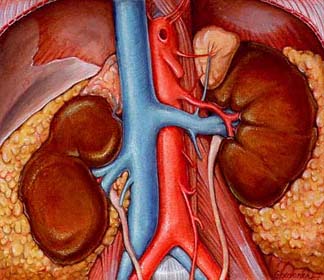

- AL amyloidosis (immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis). This is the most common type of amyloidosis in developed countries. AL amyloidosis is also called primary amyloidosis. It usually affects the heart, kidneys, liver and nerves.

- AA amyloidosis. This type is also known as secondary amyloidosis. It’s usually triggered by an inflammatory disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis. It most commonly affects the kidneys, liver and spleen.

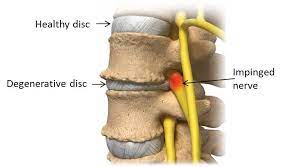

- Hereditary amyloidosis (familial amyloidosis). This inherited disorder often affects the nerves, heart and kidneys. It most commonly happens when a protein made by your liver is abnormal. This protein is called transthyretin (TTR).

- Wild-type amyloidosis. This variety has also been called senile systemic amyloidosis. It occurs when the TTR protein made by the liver is normal but produces amyloid for unknown reasons. Wild-type amyloidosis tends to affect men over age 70 and often targets the heart. It can also cause carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Localized amyloidosis. This type of amyloidosis often has a better prognosis than the varieties that affect multiple organ systems. Typical sites for localized amyloidosis include the bladder, skin, throat or lungs. Correct diagnosis is important so that treatments that affect the entire body can be avoided.”

Okay, now I was getting a little [Okay, a lot] nervous so I checked out who would be at risk for this disease. Cedars-Sinai tells us:

“The risk of developing amyloidosis is greater in people who:

- Are older than 50

- Have a chronic infection or inflammatory disease

- Have a family history of amyloidosis

- Have multiple myeloma. Between 10 and 15% of people who have multiple myeloma develop amyloidosis.

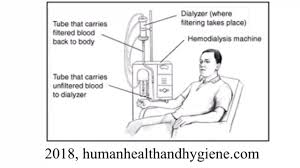

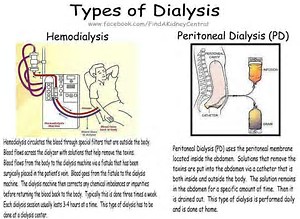

- Have a kidney disease that has required dialysis for more than five years”

Don’t panic. I’ve read again and again that dialysis has advanced to the point that fewer and fewer dialysis patients are developing amyloidosis. As usual there’s much more information available, [There’s always more.] so I urge you to visit these sites yourself if the blog has got you thinking.

Until next week,

Keep living your life!